Accumulation or blockages in storage systems and build-up in process vessels can impede material movement, causing bottlenecks that interfere with equipment performance, reduce process efficiency, and put a chokehold on an operation’s profitability. Poor material flow also raises maintenance expenses, diverting manpower from core activities and in some cases introducing safety risks for personnel.

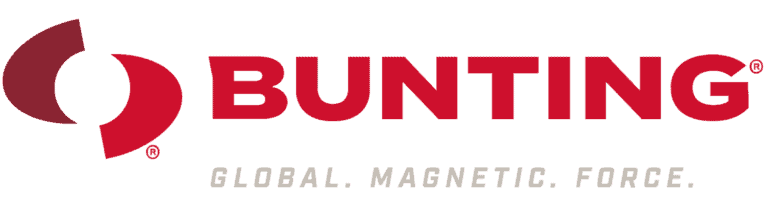

“Most systems suffer from some amount of accumulation on vessel walls, which can rob plant owners of the storage systems in which they’ve invested,” observed Brad Pronschinske, Global Director of Air Cannons Business Group for Martin Engineering. “These buildups reduce material flow, decreasing the ‘live’ capacity of the vessel, and the efficiency of the bulk handling system overall.” Pronschinske said the accumulations tend to take one of several forms: arches, plugs, build-ups, or “rat holes.”

“If they become severe enough, flow problems can bring production to a complete stop,” Pronschinske continued. Although many plants still use manual techniques to remove build-up, the cost of labor and periodic shutdowns has led some producers to investigate more effective methods for dealing with this common production issue.

Build-Up vs. Throughput

Even well-designed processes can experience accumulations, which have a significant impact on output and profitability. Changes in process conditions, raw materials, or weather can all have an effect on material flow, and even small amounts of accumulation can grow into a serious blockage.

Beyond moisture content, there are many causes of raw material buildup on vessel walls. Some metals contain naturally occurring magnetic properties. Nearly 90 percent of the earth’s crust contains silica, and the sharp crystalline structure can contribute to buildup. Other factors can include the surface friction of the silo walls, the shape of the vessel, the angle of the slope, and the size of the material being loaded.

Lost production is probably the most conspicuous cost of these flow problems, but the expense can become apparent in a variety of other ways. Shutdowns to clear the restricted flow cost the valuable process time and maintenance hours while wasting energy during re-start. Refractory walls can be worn or damaged by tools or cleaning techniques. When access is difficult, removing material blockages may also introduce safety risks for personnel. Scaffolds or ladders might be needed to reach access points, and staff can risk exposure to hot debris, dust, or gases when chunks of material are released.

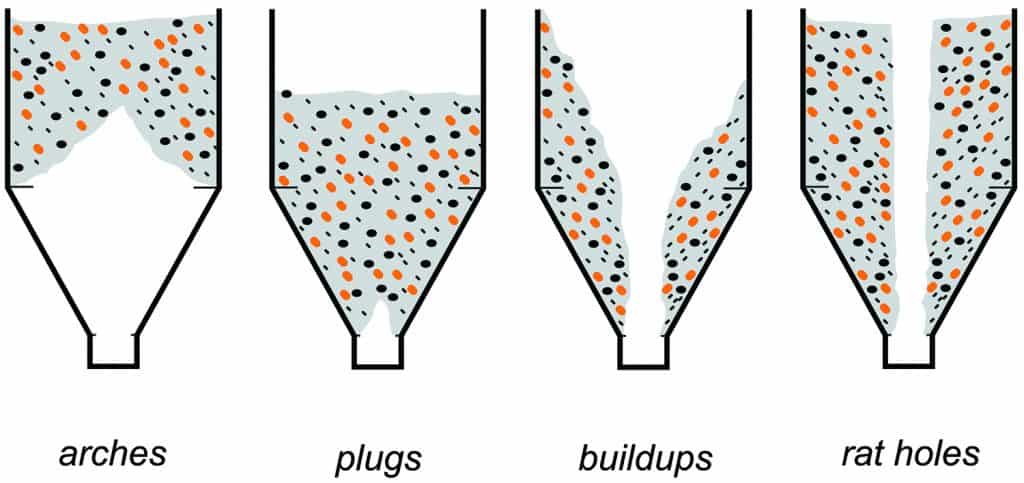

Many of the most common problem areas for accumulation are classified as confined spaces, requiring a special permit for workers to enter and perform work. The consequences of untrained or inexperienced staff entering a silo or hopper can be disastrous, including physical injury, burial, and asphyxiation. Disrupted material adhered to the sides of the vessel can suddenly break loose and fall on a worker. If the discharge door is in the open position, cargo can suddenly evacuate, causing unsecured workers to get caught in the flow. Cleaning vessels containing combustible dust — without proper testing, ventilation, and safety measures — could even result in a deadly explosion.

Getting Professional Help

“While some large facilities choose to make the capital investment to purchase their own cleaning gear to clear process equipment and storage vessels — as well as train personnel — others are finding it more sensible to schedule regular cleanings by specially-trained contractors,” said Pronschinske. “Given the costs of labor, lost time and potential risk to employees, this can often be accomplished for less than the total investment of in-house cleanouts.”

At one location, for example, the blockage was so severe in one silo that it had been out of use literally for years. While it took the outside contractor almost two weeks to fully evacuate the vessel, the process restored 3500 tons of storage capacity. At another facility, the crew was able to remove enough “lost” product that the value of the recovered material actually paid for the cost of the cleaning. In short, regular cleaning of storage vessels can quickly turn into an economic benefit — not an expense, but rather an investment with a measurable ROI.

The Costs of Cleaning

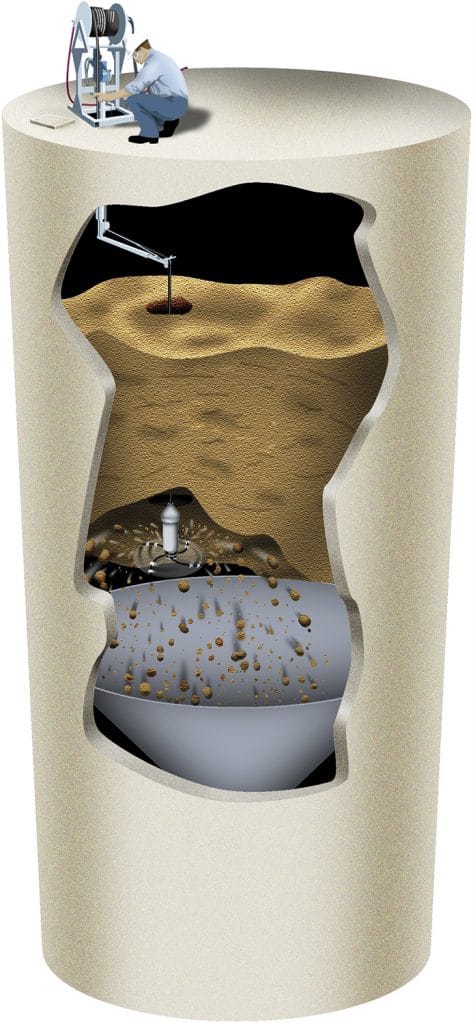

There are a few types of equipment used for this purpose. One operates like an industrial-strength “weed whip,” rotating a set of flails against the material in the vessel. This approach eliminates the need for confined space entry and hazardous cleaning techniques, typically allowing the material to be recaptured and returned to the process stream. The whip can be set up quickly outside the vessel, and it’s portable enough to move easily around various bin sizes and shapes. Typically lowered into the vessel from the top and then working from the bottom up to safely dislodge accumulation, the pneumatic cutting head delivers powerful cleaning action to remove buildup from walls and chutes without damaging the refractory. Technicians lower the device all the way down through the topside opening, then start at the bottom of the buildup and work their way up, undercutting the wall accumulation as it falls by its own weight. In extreme cases, a “bin drill” can be used to clear a 12-inch (30.5 cm) pathway as deep as 150 feet (45 meters) to start the process.

Flow Aids

Regular cleaning is one approach to keeping materials flowing freely by removing buildups from silo walls, but there are other flow aids which may reduce the need for cleaning or even eliminate it. One method is through industrial vibrators designed for bin and chute applications.

Electric vibrators are generally the most efficient, delivering the longest life, low maintenance, and low noise. The initial cost for an electric vibrator is higher than for pneumatic designs, but the operating cost is lower. Turbine vibrators are the most efficient and quietest of the pneumatic designs, making them well suited to applications in which low noise, high efficiency, and low initial cost are desired.

Air cannons are another approach to maintaining good material flow, particularly in larger vessels. Also known as an air blaster, the air cannon is a flow aid device that can be found in mining, coal handling, and many other industries. Applications vary widely, from emptying bulk material storage vessels to purging boiler ash to cleaning high-temperature gas ducts.

In the mining industry, air cannons are frequently specified to eliminate build-ups in hoppers, storage vessels, transfer chutes, bins, and other production bottlenecks. They can also be found in mineral processing plants where metals are extracted using processes creating slurries and other wet, tacky tailings.

Air cannon technology has been used in mining and material processing for many years, helping to improve flow and reduce maintenance. The timed discharge of a directed air blast can prevent accumulation or blockages that reduce process efficiency and raise maintenance expenses. In underground mines with potentially explosive dust, the manual firing of cannons without the use of electrical solenoids is an option. By facilitating the flow and minimizing build-up, air cannons help bulk material handlers minimize the need for process interruptions and manual labor.

The two basic components of an air cannon are a fast-acting, high-flow valve and a pressure vessel (tank). The device performs work when compressed air (or some other inert gas) in the tank is suddenly released by the valve and directed through a nozzle, which is strategically positioned in the tower, duct, chute, or other location. Often installed in a series and precisely sequenced for maximum effect, the network can be timed to best suit individual process conditions or material characteristics.

“The core message for mines and material processors is that they don’t have to put up with accumulation problems and the additional expenses they can cause,” Pronschinske concluded. “There are a number of approaches that can help resolve those issues before they turn into expensive downtime, lost material, and safety hazards.”